2.11 Great Uncle Charles and the Darkling Plain

...being another meandering ramble, paying visits to Ralph Vaughan Williams, Charles Darwin, Matthew Arnold and Sherlock Holmes along the way, whilst looking for relevance to our current times.

Writing these little articles takes me down all sorts of paths. Sometimes I finish a piece and realise that there are further things which demand exploration, and I need to go back for a second look. I felt that way after I wrote about The Charge of the Light Brigade. I was so taken with Maud from the same volume of Tennyson’s poetry, that I had to explore further, and create a second piece of writing. I got the same the feeling again last week after writing about Ralph Vaughan Williams, although it wasn’t a further example of his creativity which spurred me into action, it was his family history - particularly the fact that Charles Darwin was his Great Uncle.

Great Uncle Charles would only have been 63 when Ralph was born (the same age as I am as I write this) and he lived for a further ten years. In a 1960s biography of her late husband, Ursula Vaughan Williams says that when he was a boy, Ralph had asked his mother about Darwin’s work and was given the reply "The Bible says that God made the world in six days. Great Uncle Charles thinks it took longer: but we need not worry about it, for it is equally wonderful either way”

Imagine having a Great Uncle who had ignited a massive debate about science, religion and man’s place in the universe, the ramifications of which would rumble on for years and years after his death. In comparison, perhaps my most interesting relative was my Uncle John, whose main contribution to human endeavour was to get pissed and argumentative every Christmas. If only I had had a Great Uncle Charles rather than an Uncle John in the family, I would almost certainly be a National Treasure by now!

Amazingly. Vaughan Williams also had Josiah Wedgwood (of industrial revolution and quality crockery fame) amongst his forebears, which means that he must have been somehow related to the Labour Party activist Tony Benn. Perhaps I am too easily impressed by name dropping and connections, but just imagine having all that crowd in your family. And I haven’t even started on his friends, I spent a happy hour reading up on the Bloomsbury Group the other day, and felt like I had missed out on a rich life. But then I am a member of the Mexborough Read to Write Poetry Group, and I founded the Sixty Odd Poets, so I try and comfort myself by claiming that I have made a decent fist of my less than illustrious background.

Charles Darwin first expounded the theory of Evolution in On the Origin of the Species in 1859 and had driven home the point of the unexceptional position of humanity in The Descent of Man twelve years later - the year before Ralph Vaughan Williams was born. Theories of evolution had come before Darwin, but the explicit idea that man is not exceptional and in fact distinct from the animal kingdom had not been examined in any depth before Darwin. It was an idea that was as radical and Earth shattering as Copernicus’s claim that our planet was not the centre of the universe had been some three hundred years earlier.

Whatever Darwin’s views on the compatibility of evolutionary theory with The existence of a Divine creator, it certainly had a big effect on religious thought, and may be a major cause of the decrease in adherents to organised religion throughout the twentieth century and beyond. In America even today, there is still fierce debate led by creationists who believe that theories such as intelligent design should be given equal weight to evolutionary theory in schools.

Vaughan Williams himself was an agnostic, who was not averse to composing religious themed music and indeed enjoyed reading the King James Bible and religious poetry. He even regularly attended church “to avoid upsetting the family”. It would seem that whatever people do or think, there will always be a desire to somehow connect to the spiritual, and while such prominent atheists as Christopher Hitchens and Richard Dawkins may be well known and often read figures, they are perhaps seen by many as lacking something, which may be described as an appreciation of the eternal, a sense of some intangible truth that the majority of us cling onto even if it is now largely divorced from traditional organised religion.

Which leads me to the path of Matthew Arnold.

Matthew Arnold (1822-1888) was a poet who lived through the period in which Darwin was expounding his evolutionary theories. Unsurprisingly, the poetry mad Vaughan Williams set extracts from the text of a couple of his poems to music in An Oxford Elegy, a piece that he put together in the late 1940s. These were the Scholar Gypsy and the Thyarsis.1 However, it is Arnold’s Dover Beach, published in 1867, that seems to sum up the spirit of a world coming to terms with the idea that mankind is not the centre of all creation.

Arnold expresses his thoughts in the poem through the voice of someone looking out over a moonlit sea, to be precise, the English Channel. The sound of the pebbles crashing together as they are moved back and forth by the power of the waves sets up a melancholy rhythm, as he reflects that the tide is going out on a sea of faith that once protected everyone, but is now receding, leaving us on a darkling plain - alone. The speaker says to the lover who he addresses that they must be true to one another - because the world has little to offer them in the way of comfort or protection. Arnold is really addressing all of his readers - Be true to one another - because one another is all we have.

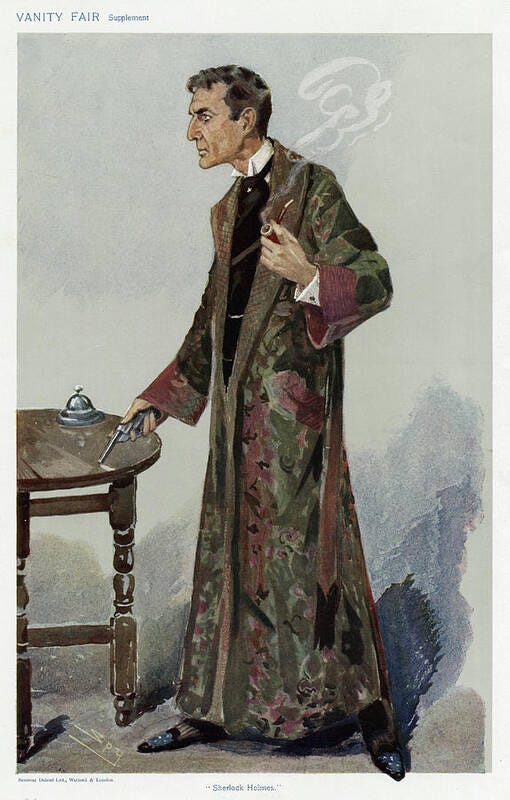

For me the poem strangely calls to mind the little speech that Sherlock Homes gives to Watson at the end of His Last Bow, written at the height of World War One, and delivered by Basil Rathbone at the end of the 1939 film adaptation Sherlock Holmes and the Voice of Terror. As they look out over a moonlit sea, Holmes tells Watson of a chill wind blowing from the East

Holmes pointed back to the moonlit sea and shook a thoughtful head….

There’s an east wind coming…

Such a wind as never blew on England yet. It will be cold and bitter, Watson, and a good many of us may wither before its blast. But it’s God’s own wind none the less, and a cleaner, better, stronger land will lie in the sunshine when the storm has cleared.

Conan Doyle - through the voice of Holmes, gives a more hopeful assessment of the future. Things are grim, but we will get through it, and come back stronger and better. Both the Arnold poem and Holmes’s speech seem to have a resonance for us today. It feels a little like the comfort and protection that was democracy may be receding with the tide, and that there is a chill wind coming from both East and West. Let’s hope that love will see us through, and we shall see a greener2, stronger, better world when the storm has cleared.

Dover Beach - by Matthew Arnold

The sea is calm tonight. The tide is full, the moon lies fair Upon the straits; on the French coast the light Gleams and is gone; the cliffs of England stand, Glimmering and vast, out in the tranquil bay. Come to the window, sweet is the night-air! Only, from the long line of spray Where the sea meets the moon-blanched land, Listen! you hear the grating roar Of pebbles which the waves draw back, and fling, At their return, up the high strand, Begin, and cease, and then again begin, With tremulous cadence slow, and bring The eternal note of sadness in. Sophocles long ago Heard it on the Ægean, and it brought Into his mind the turbid ebb and flow Of human misery; we Find also in the sound a thought, Hearing it by this distant northern sea. The Sea of Faith Was once, too, at the full, and round earth’s shore Lay like the folds of a bright girdle furled. But now I only hear Its melancholy, long, withdrawing roar, Retreating, to the breath Of the night-wind, down the vast edges drear And naked shingles of the world. Ah, love, let us be true To one another! for the world, which seems To lie before us like a land of dreams, So various, so beautiful, so new, Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light, Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain; And we are here as on a darkling plain Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight, Where ignorant armies clash by night.

Liar, Liar! Thyarsis on Fire!

I'm disinclined towards/away from religeous debate, inasmuchas it's all tosh, romaniticist though I may be. The Bloomsburies however are a different kettle of fish unto which we might cast the knife n fork of artifice. It's a period(ish when Laurie Lee skipped off to Spain, Eluned wossname travelled 1940s Wales (the Dew On The Grass) and there was I suppose an interwar bliss. Bearing in mind we had Dali, Picaso, Klimt, Mondrial and one's giddy aunt knows who else, it was quite the whizz bang deco nouveaux blues/jazz/skiffle of a time.

On the other hand, my Great Uncle Charles was a mug-maker and my unofficial Great Grandfather. Since his son, my alleged Grandfather (actual great cousin) married my paternal grandmother who 'already had a child [see my mum]'. His name was crossed out in the registry of her baptism at St Columbs' in Bradford (I spoke to the priest) it would suggest Johanes is not the biological pater of Agnes Patricianum, amen. The worry being of course that I might otherwise well have been my own cousin. Mum being born out of wedlock bothers me not a jot. It's a tradition among great Irish heroes. Not to mention feminist feezers.

To further name drop, our family was married into Twiggs and Hawleys of potty fame, our own Oliver monica carried by 'men of the cloth' who preached in chapels and the streets of Mexborough. Rather too unctiously, I gather. And much good any of that did me.

Having recently read this post I been listening to the Oxford elergy performed by the marvellous Rowan Atkinson and ,I think the Oxford philharmonic, which is extremely relaxing and a bit spine tingly, which is always a bonus.