2.28 The Poet Who Looked Into the Future

James Elroy Flecker, an Edwardian writer who brought his love of Science Fiction to poetry.

Imagine being a a promising author, playwright and poet in the prime of your life and you are struck down by a terrible illness. You could be dead in a few years. what legacy could you leave to the literary world?

In 1910 James Elroy Flecker, a writer from Lewisham, was diagnosed with Tuberculosis at the tender age of 26. Back in those days Tuberculosis was more commonly known as consumption. Some people still called it the white death. The prospects were not good.

He had just landed a good job, when he got the news, working for the British Consular Service in the Eastern Mediterranean. He had also just fallen in love with a young woman by the name of Hellé Skiadaressi. Despite his grim prognosis, she married him the next year.

Although progress was being made in understanding the disease, most advances had been made in the field of prevention. A reliable cure was a long way off1. It must have felt, as a cancer diagnosis does today, like a tap on the shoulder from the grim reaper. He only lived for five more years, succumbing to the condition in January 1915, just two months after his thirtieth Birthday.

Perhaps it was because he was made so forcibly aware of his own mortality in 1910, that he wrote what was to become perhaps his most enduring short poem – To a Poet a Thousand Years Hence.

A thousand years is a long time to look into the future. He was speaking to a poet in the year 2910, a date still almost nine hundred years from us right now. A thousand years before he wrote the poem, Britain was yet to be invaded by the Normans, The Alfred cake burning scandal was still in living memory, and King Edward the Elder was busy uniting the kingdoms of Wessex and Mercia.

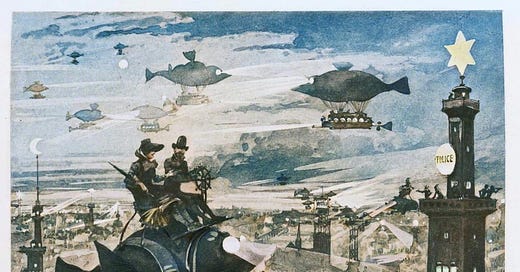

Such a span of time didn’t phase Flecker. He was a fan of science fiction. Influenced by the works of Jules Verne and HG Wells’ classic The Time Machine, he had already written a novella - The Last Generation – A Story of the Future, featuring a time travelling tale in which he foretells the death of the human race2.

To a Poet a Thousand Years Hence is more hopeful than the novella. In it, Flecker imagines that there will be still artistic minded people in the far distant future, who will understand what it is to be human and not hell bent on destruction. Perhaps that has resonance with us today too. It is good to know that there are still poets in Russia, in Israel, and in the darkening corners of America. The arts make us human, show us where we have common bonds, tell us that the throughout the world, we are all essentially the same, with magic in our souls.

It isn’t hard to imagine that Flecker is speaking of our world of today when he says.

I care not if you bridge the seas,

Or ride secure the cruel sky,

Or build consummate palaces

Of metal or of masonry.

All of these dreams were in development in 1910. The Wright Brothers had pioneered mechanical powered flight, although transatlantic passenger travel didn’t start until 1939. The land had been bought for the Empire State building, although construction wouldn’t start until 1930.

He was really speaking to his contemporaries. He was saying let’s not get carried away with all this technological advance. Let’s not forget the important things in life - wine and music, love and imagination. Perhaps our devotion to statues and prayers might have waned a bit in the time since Flecker wrote the piece, but then again, maybe he is referring to art and spirituality. If so, I am with him on all counts.

If you are a poet, or any kind of creative artist, his words will resonate for you. Never mind that you are reading it nine hundred years too early – the thousand figure is arbitrary – like sixty odd, when it was coined, it stood for an undetermined large number. And besides, unless you are over a hundred and ten years old, you would certainly have been unseen, unknown and unborn before Flecker had died (at the tender age of just 30), so he might as well have been speaking to you.

Flecker seems to be all but forgotten these days, but he managed to produce a prodigious amount of writing in his thirty years, including several volumes of poetry, two dramas, two novellas and various correspondences and factual writings. His wife, Hellé published much of it after his death, assisted by a 1930 Civil List pension3 from the government of £90 a year (worth about £7,500 today) in recognition of services rendered by her husband to poetry.

I hope that the human race is still around in the year 2910. If we have not wiped ourselves out in some ecological or military disaster, perhaps we will be scattered around the far reaches of outer space. Maybe as a part of some united federation of planets. I hope that it’s not an Empire. I hope we don’t start by conquering some distant world only to abuse and enslave its occupants before realising, years down the line, that they are sensitive, intelligent beings just like us. I would like to think that somehow, the advances in technology that we develop will allow us all to be more human, more caring and more creative and to share the best features of ourselves (wine, music and bright eyed love etc.) with who or whatever we encounter, and to develop ourselves through our interactions with them4.

To A Poet A Thousand Years Hence

I who am dead a thousand years,

And wrote this sweet archaic song,

Send you my words for messengers

The way I shall not pass along.

I care not if you bridge the seas,

Or ride secure the cruel sky,

Or build consummate palaces

Of metal or of masonry.

But have you wine and music still,

And statues and a bright-eyed love,

And foolish thoughts of good and ill,

And prayers to them who sit above?

How shall we conquer? Like a wind

That falls at eve our fancies blow,

And old Moeonides the blind

Said it three thousand years ago.

O friend unseen, unborn, unknown,

Student of our sweet English tongue,

Read out my words at night, alone:

I was a poet, I was young.

Since I can never see your face,

And never shake you by the hand,

I send my soul through time and space

To greet you. You will understand.

My favourite fun fact about tuberculosis or TB is that Ray Galton and Alan Simpson, the situation comedy writers who created Hancock’s Half Hour and Steptoe and Son met as teenagers whilst being treated for the disease in a hospital in 1948.

It is more a short story than a Novella. Around fifty pages long, it can be read online at Project Gutenberg. It is not for the faint hearted though, as it features violent executions and even a baby killing. Amusingly, an opening scene is set at Birmingham Town Hall.

The protagonist in the story does not use a time machine but is transported by some sort of personification of the wind. Perhaps like the wind that falls at eve in the poem. Old Moeonides who knew about it is a reference to Homer (the poet - not the Simpson) All that I can find about winds that blow in Homer is something about enjoying battle with the relish that sailors enjoy when blown by strong winds. But bear in mind that I am no scholar at all - I just paddle in the waters of the internet. (It’s in The Iliad at the beginning of book seven if you are interested. I got more joy out of The Last Generation, which is much shorter, and easier to understand.)

I have mentioned this sort of pension arrangement before, in the article on Walter De La Mare. Perhaps someone could put me up for one? They seem like an interesting alternative to an arts council grant. Not that I have one of those - I’m running all this on sheer enthusiasm.

Hark at me - A two bob Carl Sagan in my old age!

What a gorgeous piece of writing! (Him and you)

He wrote The Golden Journey To Samarkand (if I remember correctly) - a wonderful evocative poem, one of my favourites